LAURA STEDENFELD

Founder & Principal of Omnes, a queer- and woman-led design studio practicing in landscape architecture, planning, and art, and recipient of multiple awards from the American Society of Landscape Architects and the American Institute of Architects, among others.

Laura Stedenfeld is the founder of Omnes, a women-led design firm established in 2019 and based in the Lehigh Valley. Stedenfeld grew up in rural New Jersey, before moving to New York City to study architecture at Parsons School of Design. She spent the early part of her career practicing at OLIN, Thomas Balsley Associates, and Ohlhausen DuBois, and she was a founding member and leader at Land Collective.

Uniquely situated in the Simon Silk Mill in Easton, PA, Omnes creates beautiful designs that are ecologically-centered and born out of the communities that use them. Much like Stedenfeld's background, Omnes' projects range from "very urban to very rural," and often transcend the planning and design fields into community building and art. The studio's founding ideology of Omnes, meaning "all, everybody, together" in Latin, rings true to Stedenfeld's work, which pushes past the intangible boundaries between urban and rural to bring thoughtfully crafted designs to a diversity of communities across the country.

You've lived and practiced in the extremes of the rural to urban spectrum. How does your experience with one inform how you approach the other?

That tension of scales between rural, remote landscapes and hyper-dense downtowns is a place where my creativity has always thrived. I started my career in New York City and Philadelphia designing plazas and parks for dense metropolises, and it was a stark contrast to my upbringing in an unincorporated town in New Jersey, where the population density was merely 99 people per square mile! I spent my early life poking around the forest floor and riding my bike on dirt roads, yet I was just an hour from the museums and parks of NYC – so that split identity has always been part of my consciousness.

After nearly two decades of practicing landscape architecture and planning, I wanted to expand my concern beyond only large cities, and offer quality design/planning to rural and mid-size communities as well. It’s one of the core reasons why I started Omnes – I had a deep need to integrate my own understanding of landscape. Right now, 52% of Americans describe themselves as living in a suburban context, with 21% identifying as rural and 27% as urban. All people deserve to experience the benefits of good design and sound planning, no matter where they live. Omnes means “all” or “everybody, together” in Latin, and it perfectly encapsulates our values.

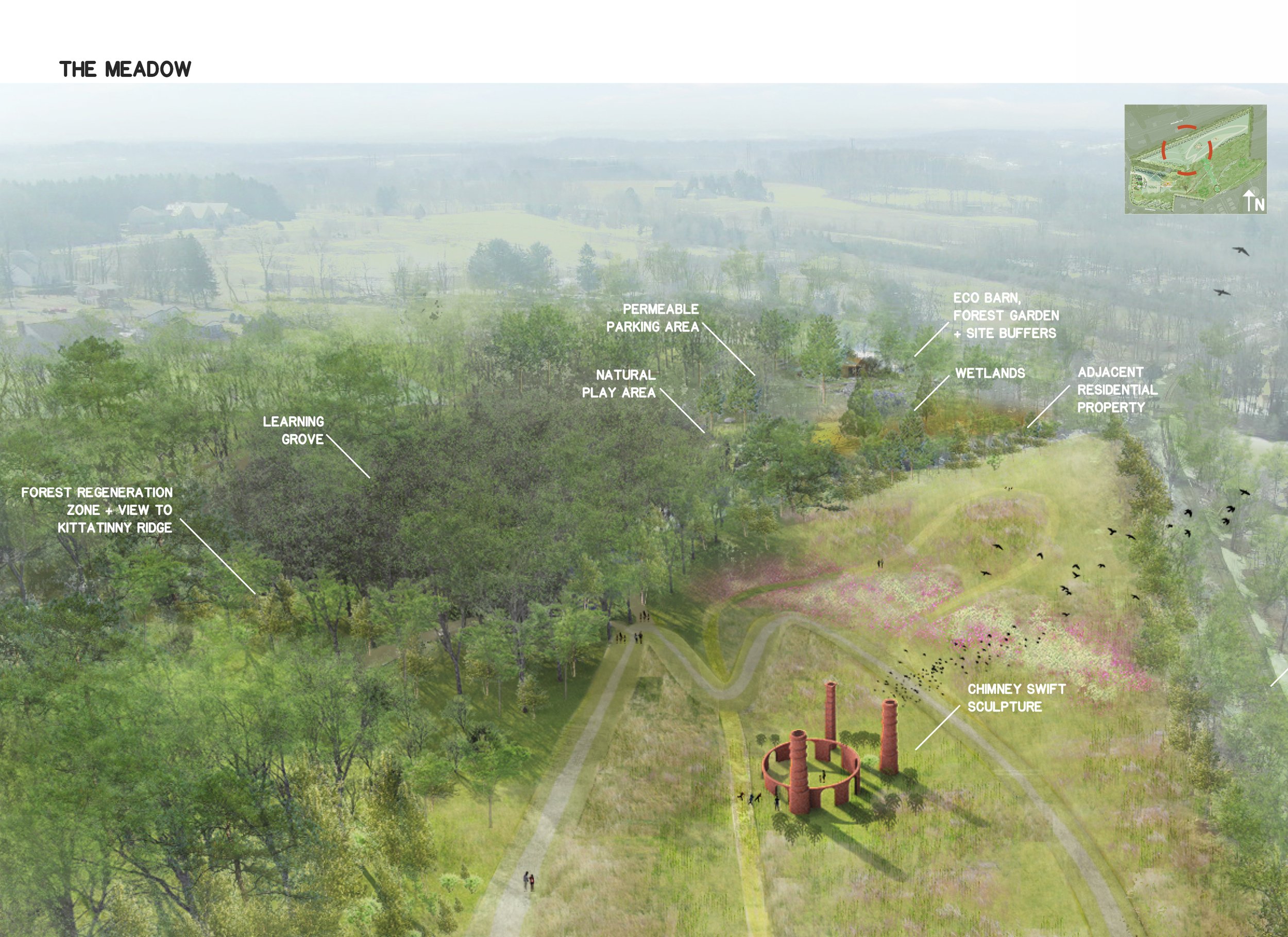

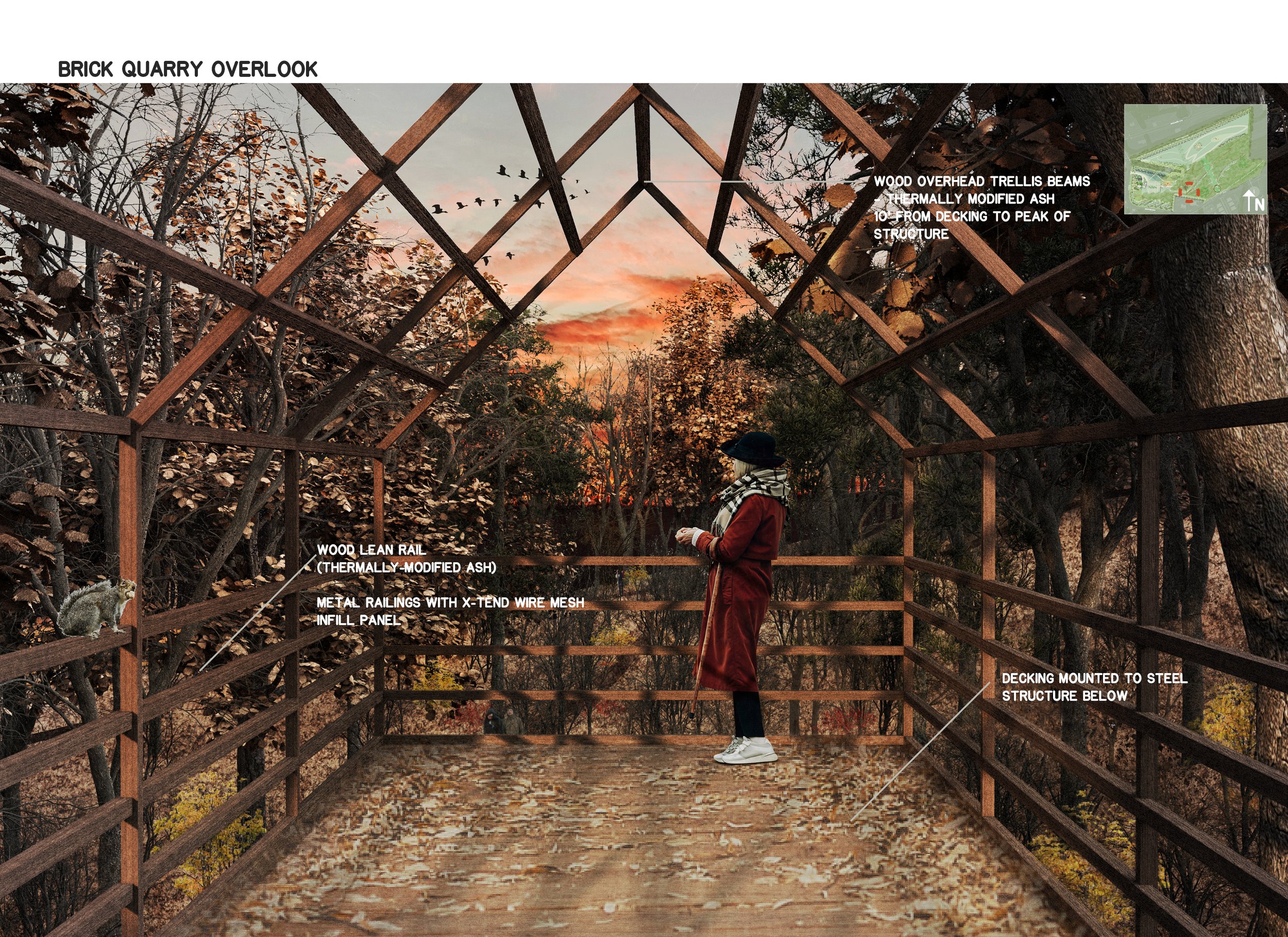

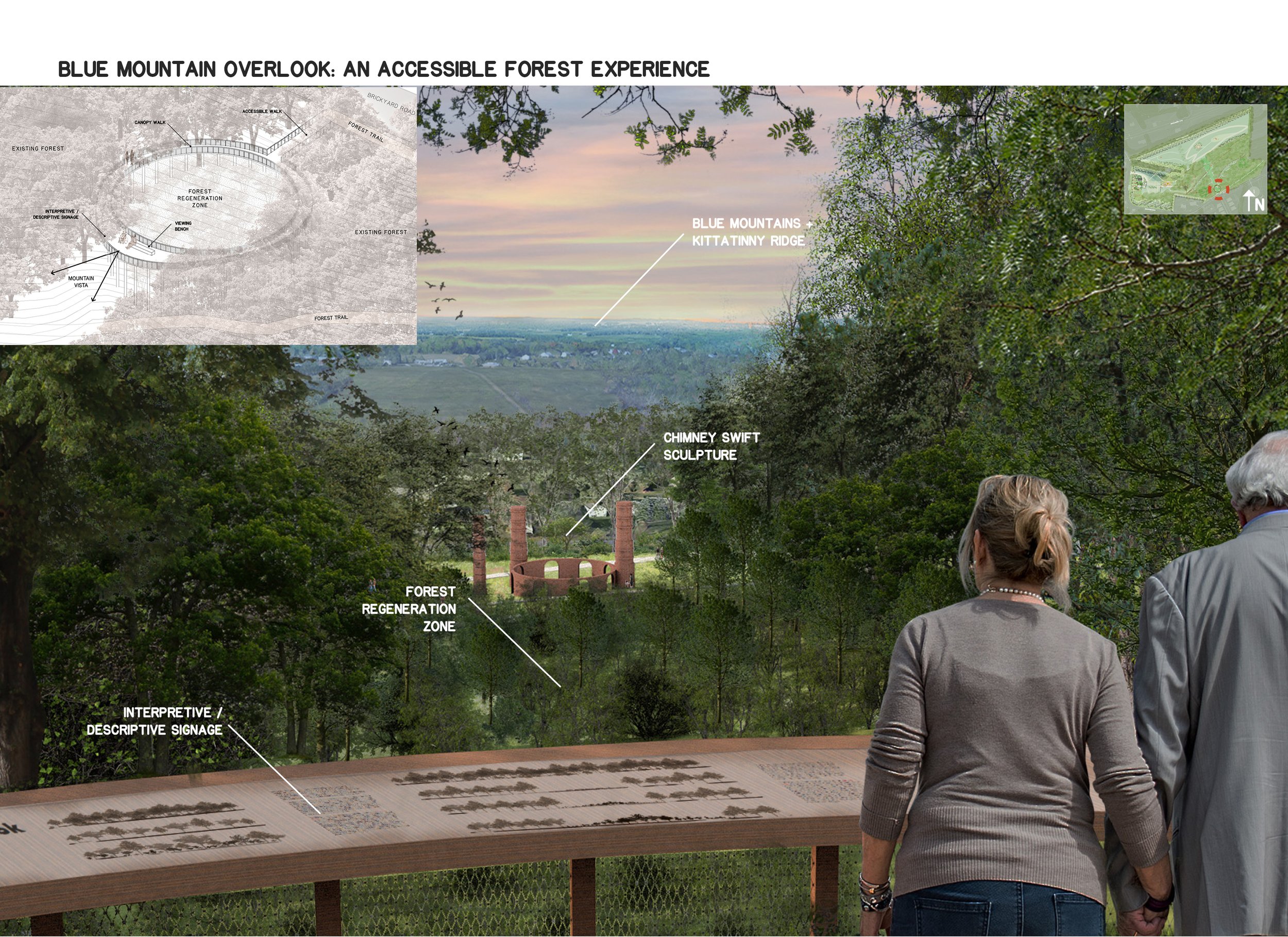

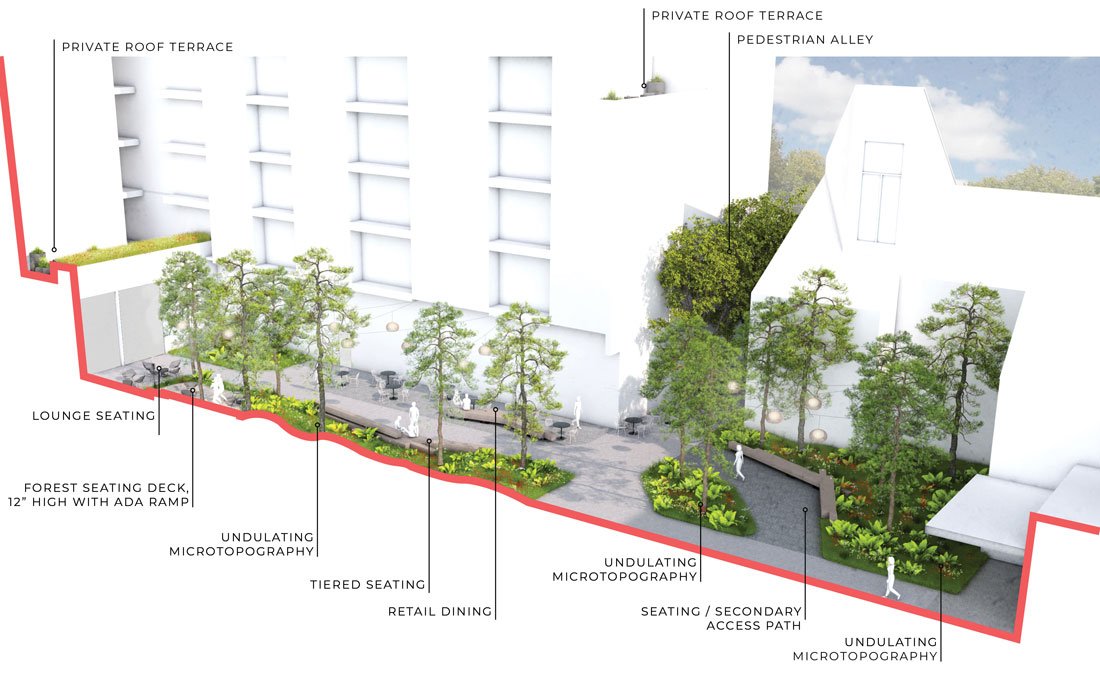

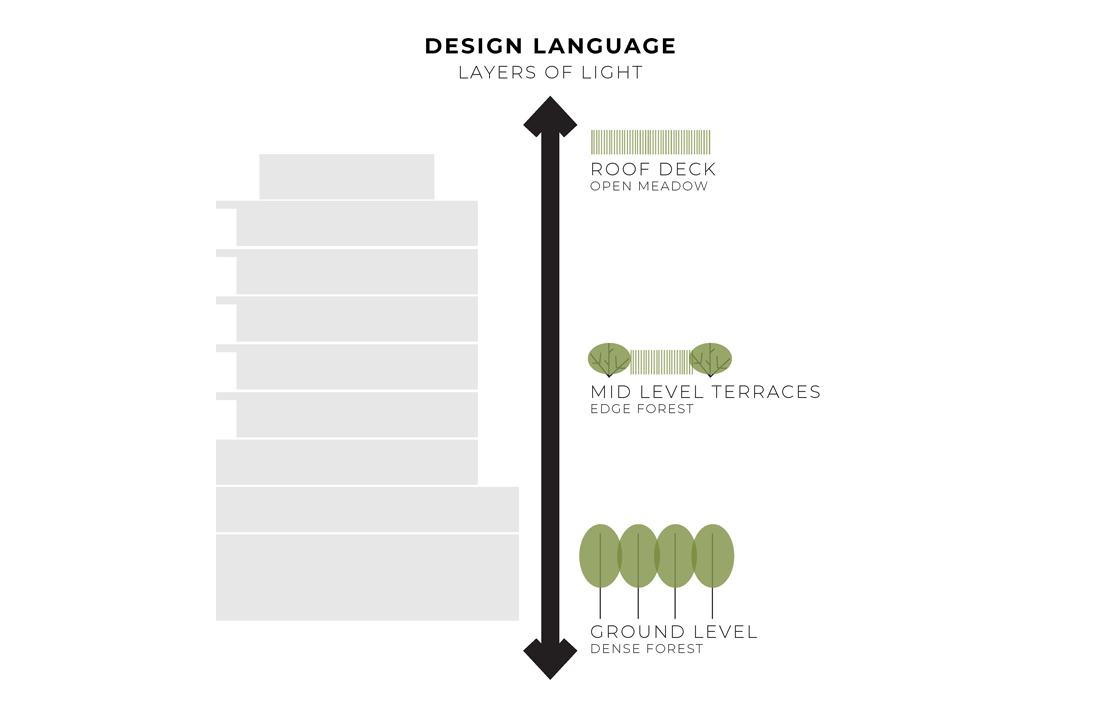

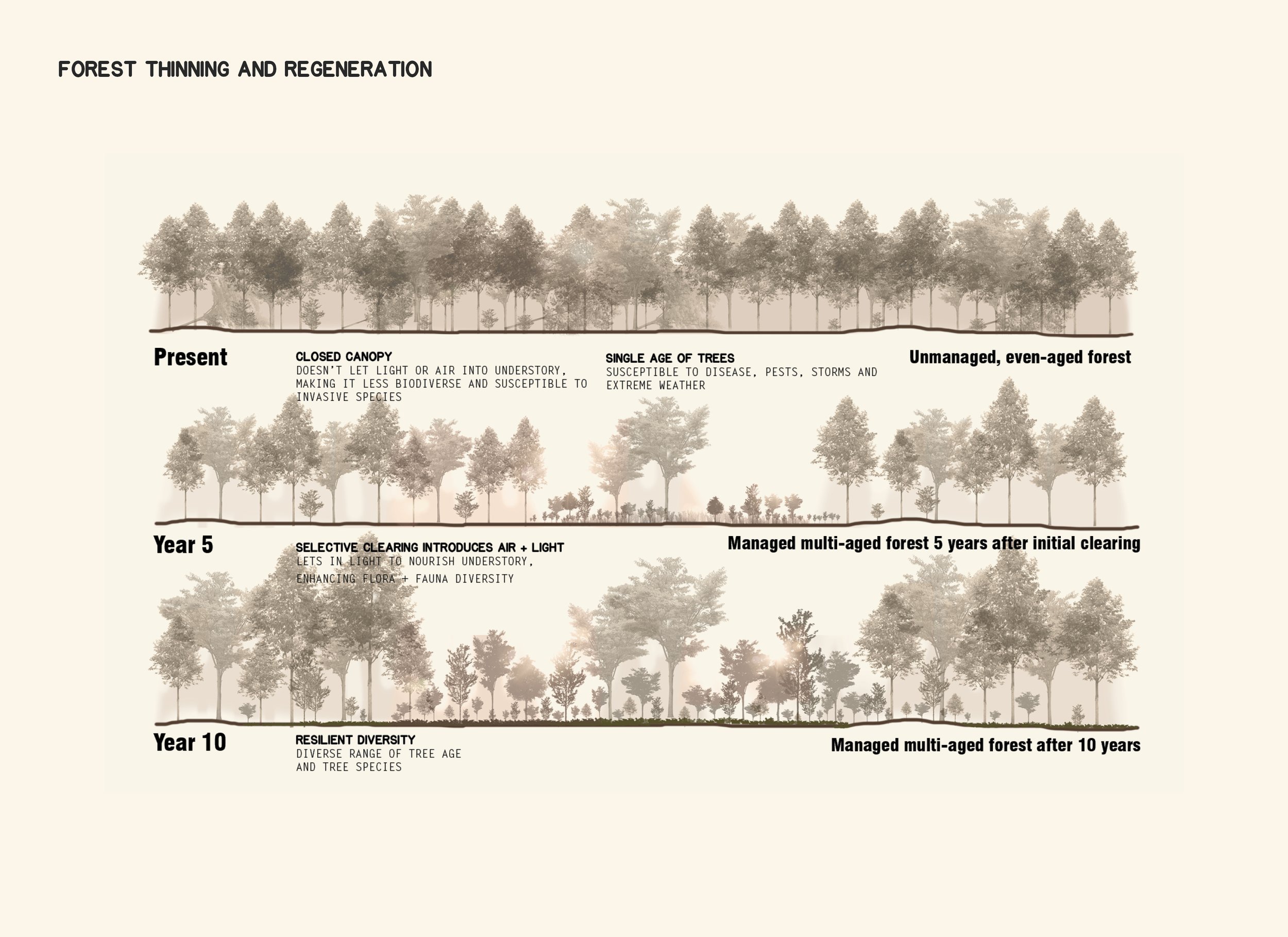

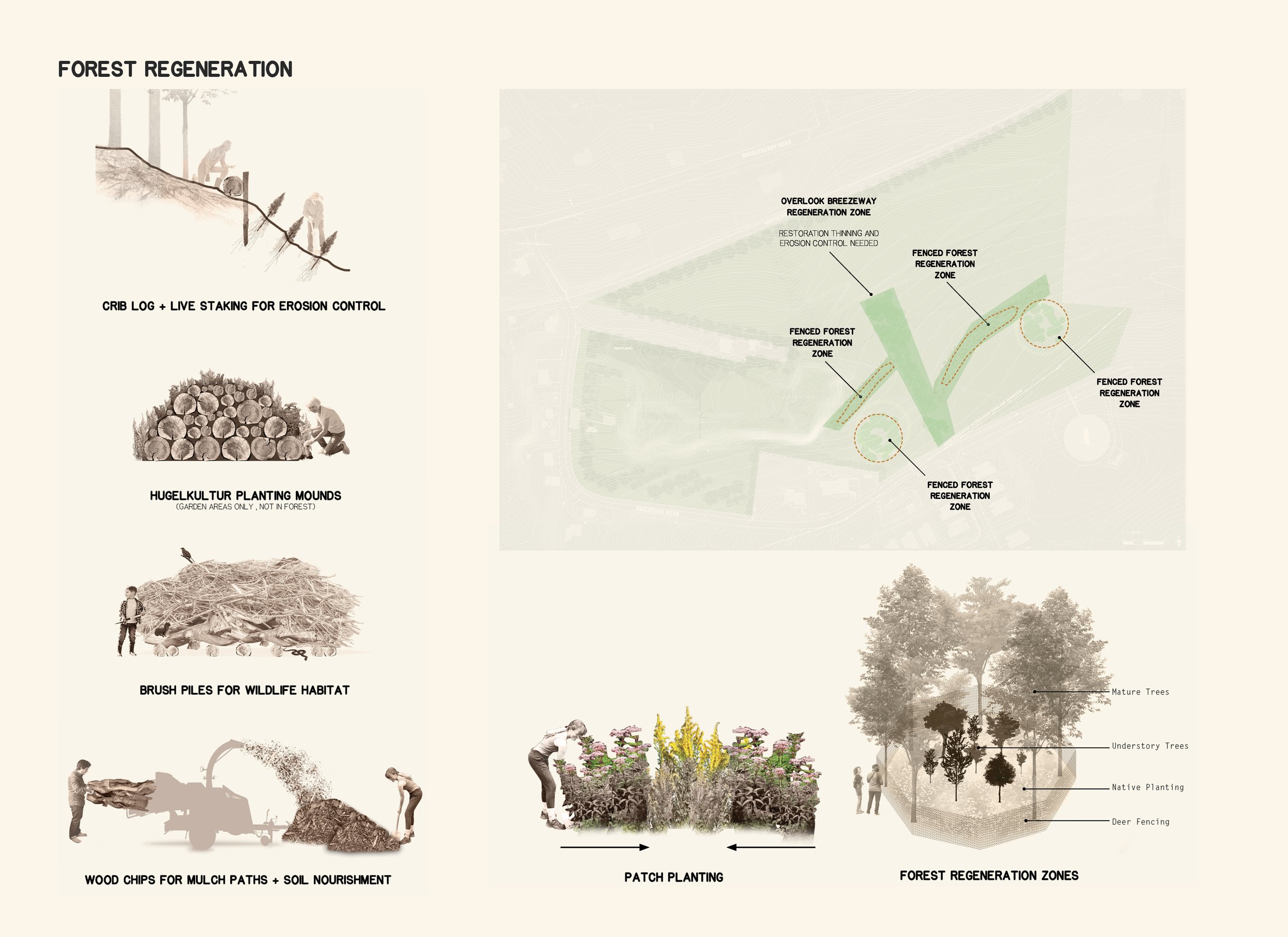

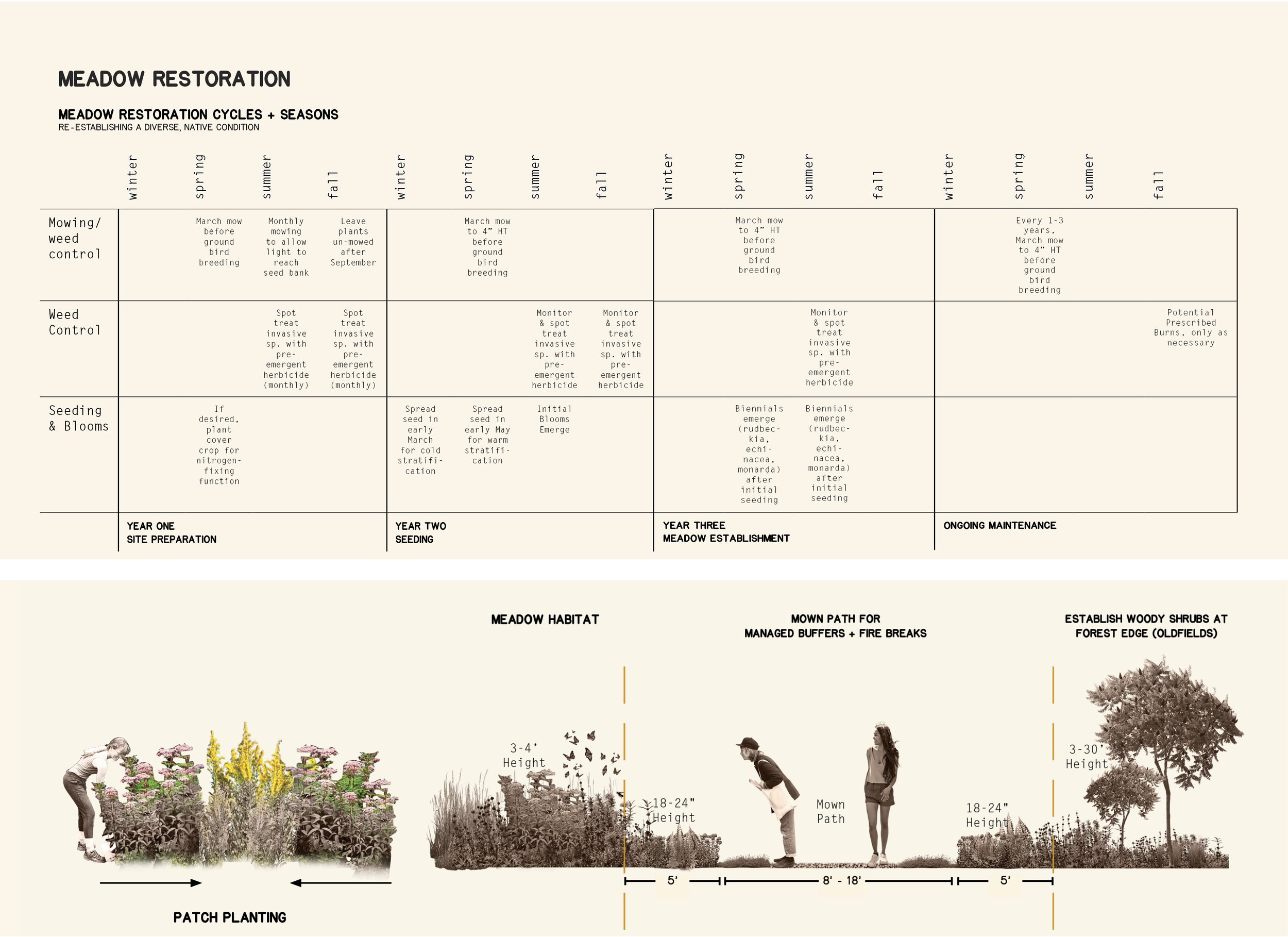

As an example of that rural-urban scale tension, we are currently working on a 26-acre passive park on a forest ridge & meadow, as well as a 1.1-million square-foot development in Philadelphia that fits within just a single city block. Toggling between these two settings creates new concepts and connections, and it makes our project work – regardless of scale – more meaningful. Experience in rural contexts has absolutely deepened our knowledge of ecological systems. I am constantly referring back to my dad’s old soil and plant biology textbooks from agronomy school, and as a studio we trek around sites identifying different fungi and geological outcroppings. Curiosity drives us, and our rural work requires us to be equally inquisitive about the landscape and the communities that sustain and steward the land. How people gather and play in cities inspires how we integrate “active” moments in rural parks, while our urban plazas and streetscapes are benefitting from a deepening of our regenerative ecological strategies. The open prairie is just as complex and fascinating as the densest downtown.

Renders from Omnes’ Kohler Ridge Park project - showing areas of forest, meadow, and post-industrial ruin activated through playful and educational moments.

Drawings of the Pitch Pine Plaza - a climate-adaptive urban plaza in Philadelphia, PA

Omnes has a unique sensibility, and it’s rooted in an underlying understanding of relational ecologies – observing and designing for the interrelationship of dynamic processes. The mutable systems of water, air, vegetative communities, and animal life are sovereign to some degree and have their own innate intelligence. Even when designed, rural ecologies such as meadows or forests are largely self-determining. You can specify plants based upon their conditions and successional aggressiveness, but ultimately the dynamics between living systems and site disturbance determine the nature of these places. They express themselves according to their own nature, just as we do as social beings. There's a humbling factor where humans aren't “in control,” but that doesn't mean we shouldn't design here – rather it's about mutuality and a relationship of observation and care.

Working in this rural-urban tension makes us confront myths about design control. Even in the densest urban plaza, you can’t possibly design for every social dynamic and completely anticipate how people will use the space. Humans are not unlike plants in the meadow, we just create different communities and densities

Rural communities are often viewed as being homogeneous. You’ve spoken about the diversity of people and values in the rural communities you’ve worked in. Can you elaborate on that experience?

Rural communities are as expansive in their values, traditions, and expressions as people living in cities! Even within communities where blocs of racial, political, economic, or social homogeneity exist, peoples’ values around land are varied, nuanced, and personal. The connecting thread across our rural and urban work is that most people want to work together to realize good ideas, and everyone wants a better life for themselves (and, hopefully, for future generations . . .).

Because people aren’t homogenous and are shaped by expansively different lived experiences, one of the most important things is for the design team and collective community to align values around how land is utilized and restored. It’s an imperative to begin any design or planning effort. For the work to be successful – to advance a larger vision of a future that’s sustainable, beautiful, and “livable” – communities also need ethical leaders and good elected governance that is truly willing to steward a collectively formed vision.

Public engagement is an act of social practice for Omnes; we’re facilitating community dialogues in a way that incorporates culture – art, music, food, and celebrations. We show up in the places where people already gather, and give them a reason to stay and talk about the future of their landscapes. I love the idea that engagement and expression of culture shifts depending on the community with whom we’re working. We rely on the guidance and knowledge of people and leaders who are already on the ground doing good work in their communities, and it’s led us to approaches that we could never have come up with on our own. We have played dominoes at a senior center; spent hours coloring and crafting with the elders of a Nepalese community while chatting with the help of a translator; given a talk at a convent; and caught a school bus with a dozen kids at 6:30 AM in 10-degree weather to hear their thoughts about parks. We’ve decorated a street with hundreds of (temporary) neon graffiti stencils and balloons; talked with community members at a festival alongside a falconer with a bus full of birds; and created an interactive art installation of 1,500 pinwheels in parks around a city during the COVID-19 health crisis. Giving away ice cream, flowers, pizza, or coffee has also proven successful just about everywhere we’ve gone. Wherever people are is where we will have discussions.

Bloom Winchester “Pops and Pizza in the Parks” Public Engagement Events

Omnes is located in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania. What are the issues facing rural communities there? How can the design community build trust with these communities and respond to the issues they face?

The Lehigh Valley is just 75 miles from both New York City and Philadelphia, and it’s the fastest growing metropolitan area in Pennsylvania. It’s also within an eight-hour drive of one-third of American consumers. Our rural/agricultural landscapes are under crushing development pressure from the rapid construction of logistical warehouses, especially cold storage. Many of the tenants are e-commerce retailers serving online shopping demand along the East Coast. It’s now common to see warehouses that are one million square feet in size, and they are sprouting up mostly in former agricultural fields. The associated decline in farming is notable, as is the fact that the structures are sited atop some of the best loamy soils in North America.

There are real concerns about what the warehousing of the Lehigh Valley will mean for the environment here, but some regional concern about development is entwined with a sense of nostalgia – many mourn the loss of bucolic agricultural landscapes and “open” spaces that once gave the countryside its character. There’s a sense that people moved to the Lehigh Valley to enjoy the vastness that rural landscapes afford, and now the very thing that defined the region is being swallowed up by urban/suburban consumerism. What this collective nostalgia elides is that just three or four lifetimes ago, these same fields were likely once old growth forests and a series of small creeks and streams in the valleys of the Appalachian Ridge. The agricultural landscape is of course not the “original” condition of the Lehigh Valley. We’re in the continuum of colonization, and it’s now pushing the limits of landscape and infrastructure to its brink.

We have to encourage municipalities and developers to act beyond economic concerns, devising new strategies that start with zoning and range from materiality to site use. We can restore ecological processes within these landscapes through hyper-dense vegetal systems. For example, dense forestation around the footprint of warehouses has the potential to offset carbon impacts and make use of this liminal scale – not quite rural, not quite industrial. We must not only work with but also go beyond existing EPA stormwater requirements; I believe we should promote investments in reforestation to introduce water- and carbon-capturing tree stands that stabilize biological function. This type of forested intervention also has the potential to close the gap between patch and corridor ecologies, ensuring that animals and insects have habitat and climate migration route access.

The Lehigh Valley is a critical link for the migration routes of birds, mammals, and amphibians in the northeast. As the climate’s variability intensifies, migration needs increase for species survival; we’re a direct path northward for species coming from the Chesapeake Bay and beyond. Anecdotally, I’m already seeing the impacts upon annual snow goose populations – many of the fields where they once gathered are now seas of single-family homes, solar arrays, warehouses, or big box stores. If we’re to preserve spaces for species other than our own, we need to introduce regenerative landscapes, offset embodied carbon of building footprints, decentralize our infrastructure grids, and densify our downtowns.

Walking the grounds of the future Kohler Ridge Park

The former Simon Silk Mill, where Omnes’ Studio is now located, in the Lehigh Valley.

What does your ideal rural countryside look like?

Rural landscapes are at the forefront of change. We can’t sustain nostalgic views of agriculture while we’re chemically destroying soil and emitting carbon at a hopeless rate. We shouldn’t valorize the innovation of electric cars when we haven’t figured out how to equitably capture solar and wind power for all. We’re not going to solve our climate crisis solely by inventing new products to be consumed – the present moment is demanding that we shift our systems, structures, and practices.

So much of our American culture is a result of technologies and strategies that were developed for/by war, from the internet to the interstate system. Technologies and chemicals made during World War II and the Vietnam War are still influencing the way we grow our food, the way we travel, how we interact, and how we educate future generations. Sometimes it feels like we’re living in a time of eventualities, where societal and ecological structures are collapsing under demands from decisions made long ago. Humans have used technology as an extension of self, pushing it to a point where we no longer recognize ourselves. As a society, we have become so removed from our own interconnectedness with the landscape, forgetting that our futures are bound together.

As a designer, these challenges make me excited to innovate. There’s a space in my mind where I imagine broken structures falling away, and we come to realize a much more regenerative society. In order to dream of a sustainable, “livable” world, we need to confront and heal from structural and internalized colonialism, and restructure our relationship to nourishment and the sublime aspects of landscape. The ideal rural countryside – the one we are collectively dreaming and designing toward – does not quite exist yet, but I see it as a landscape of networked regenerative agriculture, sustainable energy development, and preserved habitats that supports dense urban/suburban development. It has accessible, quality public transport. It would be a hybrid between the density of ecological systems in rural areas and the density of social infrastructure at the urban scale, the two coalescing upon one another.

Drawings showing adaptive restoration techniques and designs for the Kohler Ridge Park Master Plan

You have had a busy three years since starting Omnes in 2019, where is the studio going?

I have to admit, it’s been a wild ride starting a new practice amidst the converging crises of the past few years! We launched in December 2019, right before the start of the pandemic, so the studio’s early days were defined by resilience and creativity in how we collaborated.

Our work has always been about creating meaning and memory, and designing in a thoughtful way, so I feel a natural trajectory is settling into critical discussions, research, and advocacy that go beyond the landscape architect’s typical scope. Impact is really important to me at this juncture of the studio’s evolution. I’m exhausted from talking about climate change in the abstract. This moment is presenting us with such messiness to reckon with, and we are now spending some of our time imagining new ways of being. We are developing practical design tools and practices that address climate shifts, carbon capture, invasive species management, and degraded/contaminated soils. We work on a lot of brownfields and waterfront sites, so we confront those issues quite often in our work.

We’re invested in the idea that tending to landscape is a way of caring for our collective selves. We have a great little garden/living laboratory at the studio, but I’m yearning for more space to test out some of our approaches, including propagation, soil restoration, and playing with strategies for ecologically appropriate species migration. We are interested in a closer relationship with maintenance practices, so I see us moving toward a model where we have more hands-on approaches to built projects and we’re working with and training those who ultimately become stewards of the landscape.

Personally, I’m working on a collection of essays having to do with process-relational ecologies and land ethics. It’s currently a soup of words, and has taken quite a few detours during the course of the pandemic. I’m also embarking on a research/art project that I’m calling “Eisenhower’s Yellow Crayon” about the development of the American highway system, and it’s zeroing in on my fascination with the militarization of land and our culture in the US.

All images provided by Omnes Studio.